Contemplo la cruz donde está inscrito el nombre de Claus y pienso que debería sustituirla por otra que llevase el nombre de Lucas.

También pienso que pronto volveremos a estar todos juntos. Cuando muera mi madre, ya no me quedará ninguna razón para seguir.

Venimos de la gran ciudad. Hemos viajado toda la noche. Nuestra madre tiene los ojos rojos. Lleva una caja de cartón grande y nosotros dos una maleta pequeña cada uno con su ropa, además del diccionario grande de nuestro padre, que nos vamos pasando cuando tenemos los brazos cansados.

Andamos mucho rato. La casa de la abuela está lejos de la estación, en la otra punta del pueblo. Aquí no hay tranvía, ni autobús, ni coches. Solo circulan algunos camiones militares.

Apenas hay transeúntes, el pueblo está silencioso. Se oye el ruido de nuestros pasos; caminamos sin hablar, nuestra madre en medio, entre nosotros dos.

Nuestra madre dice:

—No le pido nada para mí. Solo me gustaría que mis hijos sobreviviesen a esta guerra. Bombardean la ciudad día y noche, y ya no hay nada que comer. Evacúan a los niños al campo, a casa de parientes o de extraños, a cualquier sitio.

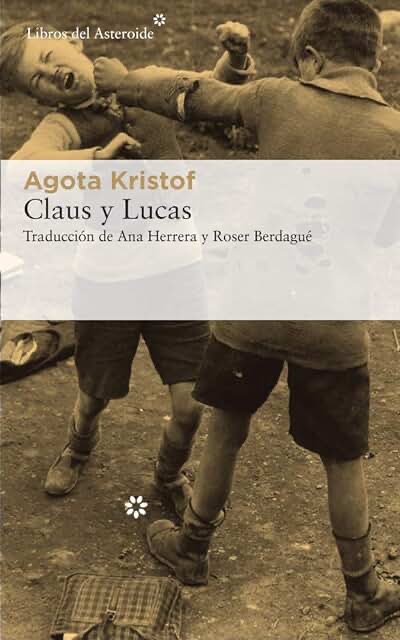

Un libro muy negro como pocos, absolutamente fuera del molde clásico. No le da al lector ni un momento de respiro.

No tiene sentido hablar de la trama, porque cuando crees entender cómo se desarrolla la historia, avanzas y las pocas certezas que creías tener se derrumban como castillos de arena.

Está dividido en tres partes. El primero, “el gran cuaderno”, es, en mi opinión, el más bonito. Pero también el más negro, el más duro y el más trágico. Frases cortas y secas que simplemente cuentan hechos, como muchas instantáneas de degradación y depravación: guerra, muerte, crueldad, soledad y desesperación. Ninguna referencia espacio-temporal, no sólo en la primera parte, sino a lo largo de todo el libro, lo que sirve para acentuar la tragedia y la impersonalidad de los acontecimientos.

En la segunda parte, «La prueba», el estilo cambia ligeramente, en el sentido de que aparecen nuevos personajes que entran en escena sin previo aviso y con la misma rapidez desaparecen en los meandros de la vida, los períodos se alargan. Sin embargo, la confusión del lector aumenta. Es difícil seguir los acontecimientos porque los personajes intercambian roles, los muertos no están muertos, las víctimas se convierten en verdugos. ¿Cuál es la verdad, si la hay? ¿Cuál es la mentira? “Cuando la historia se vuelve insoportable por su verdad hay que cambiarla…”

En la tercera parte, «la tercera mentira» todo se mezcla y ya no sabemos quién dijo la verdad, desde qué punto de vista conocimos los hechos; como sucede en la vida, que no permite una visión unívoca sino que carece de sentido, el reino de la incomunicabilidad y la soledad.

Y cuando llegues al final tendrás que respirar profundamente para recuperarte.

Quizás el comentario más significativo sea la frase contenida en el final, que aniquila: «la vida es de total inutilidad, es un disparate, una aberración, un sufrimiento infinito, la invención de un no-Dios de un mal que supera la imaginación».

Un libro muy bonito y atractivo que te impacta profundamente.

Ágota Kristof vivió una guerra pero escribe sus novelas como si fueran un sueño. Nunca estamos seguros de qué es real y qué es imaginado, dónde termina la verdad y dónde comienzan las mentiras. Gemelos con una sola voz, una vida en común; bien podría ser sólo una persona la que sueña; un alma solitaria y llena de cicatrices que no puede soportar la soledad y el tormento. Y, sin embargo, el sueño podría ser cierto; nunca podemos estar seguros. Tres versiones de la misma verdad. Podríamos traspasar el velo de las mentiras y vislumbrar la pura verdad. Pero es posible que no nos encontremos en la dimensión correcta; una verdad en un mundo podría ser una mentira en el otro.

¿Y si viviéramos en un sueño? Su realidad es diferente a la que encontramos cuando estamos despiertos. A veces desearía poder vivir un poco más en el reino de mis sueños. Ciudades misteriosas, aventuras increíbles. Pudiendo patear el suelo y elevarse en el aire, volando sobre la ciudad. Deberíamos poder elegir la realidad que deseamos, la que nos haga felices. Deberíamos poder vivir en la realidad de nuestros sueños: nuestra mente no necesita nuestro cuerpo débil allí.

Los gemelos hacen todo juntos, sus voces son una. Su voluntad ya es fuerte, no se inclina hacia nadie. Ayudan si sienten que está justificado, pero nunca porque se lo pidan. Una corrección sin escrúpulos hasta el más mínimo detalle. Y, lo más importante de todo, ejercicios para endurecer el cuerpo y el espíritu. Aprenden a afrontar el hambre, el dolor, la injusticia; aprenden a vivir con la crueldad y la muerte; aprenden lo que es ser ciego y sordo.

Observan y nunca juzgan, pero recurren a la venganza cuando la merecen; su ley es la ley del Antiguo Testamento. Aceptan cada experiencia sin pestañear ni asombrarse; observan y aprenden. Recorren el camino de la crueldad y la promiscuidad, ¿o es el camino que conduce a la vida primitiva, a la naturaleza original del hombre? ¿Son sociópatas o representan al hombre nuevo, producto de un mundo en guerra?

Los gemelos desafían el terror que los rodea. Tienen su propio camino, su propia ley. Se sienten más asustados en un sótano abarrotado que deambulando por calles desiertas, rodeados de bombas y aviones. ¿Valentía, imprudencia o quizás indiferencia? Vemos la guerra a través de sus ojos: los soldados extranjeros, la deportación de judíos, las atrocidades cometidas. Es un mundo retorcido con una fealdad, una crueldad y una depravación distorsionadas hasta el punto de volverse absurdas, irracionales y repugnantes. Los gemelos se ven rodeados por una nueva ciudad, Babel, donde prevalece la ley de la supervivencia.

Esta novela es una de las más tristes e impactantes que he leído. Pero el libro más triste nunca puede ser más triste que una vida, dice Kristof. ¿Cuánto puede soportar un ser humano? Si buscas un sentido a la vida, no lo hay, dice. ¿Qué pasa con el amor, el elixir universal de la felicidad? Los gemelos excluyen de sus vidas la palabra y la noción de amor. Pero ¿cuál es el vínculo entre ellos si no es el amor? Sus experimentos niegan los sentimientos y las debilidades humanas; desafían el hambre, la compasión, el apego. Van aún más lejos: intentan romper su vínculo. Intentan el experimento definitivo, dividir un ser en dos mitades. Ya no se trata de felicidad, porque la pregunta importante es: ¿podrán sobrevivir los dos seres? ¿Saben vivir a su manera?

Lee esta novela. Léelo y experimenta el dolor y la tristeza. Estarás enfermo, disgustado, atormentado. Cuando cierres el libro, te darás cuenta de que no podrás sonreír por un tiempo. Sentirás que realmente has vivido una guerra. Sobreviviste, pero preferirías estar muerto. El mundo de las mentiras ya no será suficiente. Una buena relectura cada cierto tiempo.

La abuela es la madre de nuestra madre. Antes de venir a vivir a su casa no sabíamos que nuestra madre aún tenía madre.

Nosotros la llamamos abuela.

La gente la llama la Bruja.

Ella nos llama «hijos de perra».

La abuela es menuda y flaca. Lleva una pañoleta negra en la cabeza. Su ropa es gris oscuro. Lleva unos zapatos militares viejos. Cuando hace buen tiempo va descalza. Su cara está llena de arrugas, de manchas oscuras y de verrugas de las que salen pelos. Ya no tiene dientes, al menos que se vean.

La abuela no se lava jamás. Se seca la boca con la punta de la pañoleta cuando ha comido o ha bebido. No lleva bragas. Cuando tiene que orinar, se queda quieta donde está, separa las piernas y se mea en el suelo, por debajo de la falda.

La abuela nos pega a menudo con sus manos huesudas, con una escoba o un trapo mojado. Nos tira de las orejas, nos agarra por el pelo.

Otras personas también nos dan bofetadas y patadas, no sabemos muy bien por qué.

Los golpes duelen, nos hacen llorar.

Las caídas, los arañazos, los cortes, el trabajo, el frío y el calor también son causa de sufrimiento.

Decidimos endurecer nuestro cuerpo para poder soportar el dolor sin llorar.

La abuela nos dice:

—¡Hijos de perra!

La gente nos dice:

—¡Hijos de Bruja! ¡Hijos de puta!

Otros nos dicen:

—¡Imbéciles! ¡Golfos! ¡Mocosos! ¡Burros! ¡Marranos! ¡Puercos! ¡Gamberros! ¡Sinvergüenzas! ¡Pequeños granujas! ¡Delincuentes! ¡Criminales!.

Nuestra vecina es una mujer menos vieja que la abuela. Vive con su hija en la última casa del pueblo. Es una casucha completamente en ruinas, con el tejado agujereado en muchos sitios. Alrededor hay un jardín, pero no está cultivado como el jardín de la abuela. Solo crecen malas hierbas.

La vecina se pasa el día sentada en un taburete en su jardín mirando al frente, no se sabe qué. Al atardecer, o cuando llueve, su hija la coge por el brazo y la hace entrar en la casa. A veces su hija se olvida o no está, y entonces la madre se queda fuera toda la noche, haga el tiempo que haga.

La gente dice que nuestra vecina está loca, que perdió el juicio cuando el hombre que le hizo la hija la abandonó.

Conocemos a otros niños en el pueblo. Como la escuela está cerrada, pasan todo el día fuera. Hay mayores y pequeños. Algunos tienen aquí su casa y su madre, otros vienen de lejos, como nosotros. Sobre todo de la ciudad.

Muchos de esos niños están en casa de personas a las que antes no conocían. Deben trabajar en los campos y las viñas; la gente que los cuida no siempre es amable con ellos.

Los niños mayores a menudo atacan a los más pequeños. Les cogen todo lo que llevan en los bolsillos y a veces incluso les quitan la ropa. También les pegan, sobre todo a los que vienen de fuera. Los niños de aquí están protegidos por su madre y jamás salen solos.

A nosotros no nos protege nadie. De modo que aprendemos a defendernos de los mayores.

La noche a la mañana, aparecen unos carteles en las paredes del pueblo. En uno de ellos, se ve a un anciano tirado en el suelo con el cuerpo traspasado por la bayoneta de un soldado enemigo. En otro cartel, un soldado enemigo golpea a un niño con otro niño que sujeta por los pies. En otro cartel, un soldado enemigo tira del brazo de una mujer y con la otra mano le desgarra la blusa. La mujer tiene la boca abierta y las lágrimas le corren por las mejillas.

La gente que mira los carteles se queda aterrorizada.

La abuela se ríe y dice:

—Qué mentiras. No tengáis miedo.

La gente dice que la ciudad ha caído.

De vuelta a casa de la abuela, Lucas se acuesta junto a la cerca del jardín, a la sombra de los arbustos. Espera. Un vehículo del ejército se detiene ante el edificio de los guardias de frontera. Bajan unos militares y dejan en el suelo un cuerpo envuelto en una lona de camuflaje. Un sargento sale del edificio, hace una señal y los soldados apartan la lona. El sargento silba.

—¡Identificarlo no será pan comido, desde luego! ¡Hay que ser imbécil para intentar pasar esta puta frontera y además en pleno día!.

Estoy en la cárcel de la pequeña ciudad de mi niñez.

No es una verdadera cárcel, sino una celda en el edificio de la policía local, un edificio que es una casa más del pueblo, una casa de un solo piso.

Antaño la celda debía de ser un lavadero, pues la puerta y la ventana dan al patio. Los barrotes de la ventana se añadieron en la parte interior para que fuera imposible alcanzar el cristal y romperlo. En un rincón, detrás de una cortina, está el retrete. Arrimada a una de las paredes, hay una mesa y cuatro sillas atornilladas al suelo y, en la pared de enfrente, cuatro camas abatibles. Tres de ellas están bajadas.

Estoy solo en la celda. En esta ciudad hay pocos delincuentes y, cuando aparece alguno, lo trasladan inmediatamente a la ciudad vecina, que es la capital de la región, a veinte kilómetros de aquí.

Yo no soy un delincuente. Si estoy aquí es porque no tengo los papeles en regla y mi visado ha caducado. Además, he contraído deudas…

El 30 de octubre, celebro mi cumpleaños en una de las tabernas más populares de la ciudad con mis compañeros de copas. Todos me invitan a beber. Hay parejas que bailan al son de mi armónica. Algunas mujeres me besan. Estoy borracho. Empiezo a hablar de mi hermano, como siempre que bebo demasiado. Toda la ciudad conoce mi historia: busco a mi hermano, con quien viví aquí hasta los quince años. Tengo que encontrarlo aquí, lo espero, sé que volverá cuando se entere de que he regresado del extranjero.

Todo es mentira. Sé perfectamente que en esta ciudad, en casa de la abuela, yo vivía solo, que ya entonces imaginaba que éramos dos, mi hermano y yo, para hacer soportable la insoportable soledad.

Siempre éramos cuatro en la mesa: nuestro padre, nuestra madre y nosotros dos.

Nuestra madre se pasaba el día cantando. En la cocina, en el jardín, en el patio. También cantaba por la noche, en nuestro cuarto, para que nos durmiéramos.

Nuestro padre no cantaba. A veces silbaba mientras partía leña para la cocina. Por la tarde, e incluso muy entrada la noche, le oíamos teclear en su máquina de escribir.

Era un ruido agradable y tranquilizador como una música, como la máquina de coser de nuestra madre, como el ruido de platos, como el canto de los mirlos en el jardín, como el viento en las hojas de la parra silvestre que teníamos en la galería o en las ramas del nogal que crecía en el patio.

Cuando mi madre recibe el dinero, la pequeña cantidad de dinero que le da el Estado, va a la ciudad y vuelve cargada de juguetes caros, que esconde debajo de la cama de Lucas. Me lo advierte:

No toques nada. Esos juguetes deben estar nuevos cuando vuelva Lucas.

Ahora ya sé qué medicamentos toma mi madre.

La enfermera me lo ha explicado todo.

Así, cuando no quiere tomarlos o se olvida, se los pongo en el café, en el té o en la sopa.

Sois hermanos, no lo olvides, Klaus. No podéis amaros de la manera que os amasteis. No habría debido llevarte a casa.

Digo:

—¿Qué importa que seamos hermanos? No lo sabría nadie. Tenemos un apellido diferente.

—No insistas, Klaus, no insistas. Olvídate de Sarah.

No digo nada. Antonia añade:

—Espero un niño. Me he vuelto a casar.

Digo:

—Quieres a otro hombre, llevas otra vida. ¿Por qué sigues viniendo al cementerio?

—No lo sé, quizá lo hago por ti. Fuiste mi hijo durante siete años.

Mi madre apenas tiene dinero. Recibe una pequeña cantidad del Estado en concepto de invalidez. Yo soy una carga más para ella. Debo encontrar un trabajo cuanto antes. Véronique me propone repartir periódicos.

Me levanto a las cuatro de la madrugada, voy a la imprenta, recojo el fajo de periódicos, recorro las calles que tengo asignadas, dejo los periódicos delante de las puertas, en los buzones o debajo de las persianas de hierro de las tiendas.

Mi madre me reprocha continuamente que haya abandonado la escuela.

Lucas habría continuado los estudios. Habría sido médico. Un gran médico.

Cuando el agua se cuela por el tejado de nuestra ruinosa casa, mi madre dice:

Lucas habría sido arquitecto, un gran arquitecto.

Cuando le enseño mis primeros poemas, mi madre los lee y dice:

Lucas habría sido escritor, un gran escritor.

I look at the cross where Claus’s name is inscribed and I think that I should replace it with another one that bears Lucas’s name.

I also think that soon we will all be together again. When my mother dies, I will have no reason to continue.

We come from the big city. We have traveled all night. Our mother has red eyes. She carries a large cardboard box and the two of us carry a small suitcase each with her clothes, as well as our father’s large dictionary, which we pass around when our arms are tired.

We walked for a long time. Grandma’s house is far from the station, on the other side of town. There is no tram, no bus, no cars here. Only some military trucks circulate.

There are hardly any passersby, the town is silent. You can hear the noise of our steps; We walk without speaking, our mother in the middle, between the two of us.

Our mother says:

—I don’t ask you for anything for me. I just wish my children survived this war. They bomb the city day and night, and there is nothing to eat anymore. They evacuate children to the countryside, to relatives’ or strangers’ homes, anywhere.

A very dark book like few others, absolutely outside the classic mold. It doesn’t give the reader a moment’s respite.

There is no point in talking about the plot, because when you think you understand how the story develops, you move forward and the few certainties you thought you had collapse like sand castles.

It is divided into three parts. The first, “the big notebook”, is, in my opinion, the most beautiful. But also the blackest, the hardest and the most tragic. Short, dry sentences that simply tell facts, like many snapshots of degradation and depravity: war, death, cruelty, loneliness and despair. No space-time reference, not only in the first part, but throughout the entire book, which serves to accentuate the tragedy and impersonality of the events.

In the second part, «The Test», the style changes slightly, in the sense that new characters appear and enter the scene without warning and just as quickly disappear in the meanders of life, the periods lengthen. However, the reader’s confusion increases. It is difficult to follow the events because the characters exchange roles, the dead are not dead, the victims become executioners. What is the truth, if any? What is the lie? “When history becomes unbearable because of its truth, it must be changed…”

In the third part, «the third lie» everything is mixed and we no longer know who told the truth, from what point of view we learned the facts; as happens in life, which does not allow a univocal vision but lacks meaning, the realm of incommunicability and loneliness.

And when you get to the end you will have to take a deep breath to recover.

Perhaps the most significant comment is the phrase contained in the ending, which annihilates: «life is of total uselessness, it is nonsense, an aberration, infinite suffering, the invention of a non-God of an evil that surpasses imagination».

A very beautiful and attractive book that impacts you deeply.

Ágota Kristof lived through a war but she writes her novels like they were a dream. We are never sure what is real and what is imagined, where the truth ends and where the lies start. Twins with a single voice, a common life; it could well be just one person who dreams; a lonely, scarred soul that can’t bear the loneliness and torment. And yet the dream might be true; we can never be sure. Three versions of the same truth. We could pierce through the veil of lies and take a glimpse of the bare truth. But we might not find ourselves in the right dimension; a truth in one world could be a lie in the other.

What if we lived in a dream? Its reality is different than the one we find when awake. I sometimes wish I could live a bit longer in the realm of my dreams. Mysterious cities, incredible adventures. Being able to kick the ground and rise in the air, flying above the city. We should be able to choose the reality we desire, the one that makes us happy. We should be able to live in the reality of our dreams – our mind does not need our weak body there.

The twins do everything together, their voices are one. Their will is already strong, bent to no one. They help if they feel it is justified, but never because of being asked. An unscrupulous correctness down to the smallest details. And, more important of all, exercises to toughen the body and spirit. They learn to face hunger, pain, injustice; they learn to live with cruelty and death; they learn what it is to be blind and deaf.

They observe and never judge, but they resort to vengeance when deserved; their law is the Old Testament law. They accept every experience without a flinch or wonder; they observe and learn. They tread the path of cruelty and promiscuity – or is it the path that leads to primitive life, to the original nature of man? Are they sociopaths or do they represent the new man, the product of a world at war?

The twins defy the terror around them. They have their own path, their own law. They feel more scared in a crammed cellar than roaming the deserted streets, surrounded by bombs and soaring planes. Valiance, recklessness, or maybe it is indifference? We perceive the war through their eyes – the foreign soldiers, the deportation of Jews, the atrocities committed. It is a twisted world with an ugliness, cruelty and depravity distorted to the point where it becomes absurd, irrational, sickening. The twins are surrounded by a new town of Babel, where the law of survival prevails.

This novel is one of the saddest and most shocking I’ve read. But the saddest of books can never be sadder than a life, Kristof says. How much can a human being endure? If you search for a meaning of life, there is none, she says. What about love, the universal elixir of happiness? The twins exclude the word and the notion of love from their lives. But what is the bond between them, if it is not love? Their experiments deny human feelings and weaknesses; they challenge hunger, pity, attachment. They go even further – they try to break their bond. They attempt the ultimate experiment, dividing one being into two halves. It’s no longer a matter of happiness, because the important question is: can the two beings survive? Do they know how to live on their own separate way?

Read this novel. Read it and experience the pain and the sadness. You’ll be sick, disgusted, tormented. When you’ll close the book, you’ll realize you won’t be able to smile for a while. You’ll feel like you’ve really lived through a war. You survived, but you’d rather be dead. The world of lies won’t suffice anymore. A good re-read again.

Grandma is our mother’s mother. Before she came to live in her house, we didn’t know that our mother still had a mother.

We call her grandmother.

People call her the Witch.

She calls us «sons of bitches.»

The grandmother is small and skinny. She wears a black scarf on her head. Her clothes are dark gray. She is wearing old military shoes. When the weather is good she goes barefoot. Her face is full of wrinkles, dark spots and warts with hair growing out of them. She no longer has teeth, unless you can see them.

Grandma never washes herself. She wipes her mouth with the end of her scarf when she has eaten or drunk. She’s not wearing panties. When she has to urinate, she stays where she is, she spreads her legs and pees on the floor, under her skirt.

Grandma often hits us with her bony hands, with a broom or a wet rag. She pulls our ears, she grabs us by the hair.

Other people also slap and kick us, we don’t really know why.

The blows hurt, they make us cry.

Falls, scratches, cuts, work, cold and heat are also causes of suffering.

We decided to toughen our body to be able to endure the pain without crying.

Grandma tells us:

—Sons of bitches!

People tell us:

—Sons of Witches! Sons of bitches!

Others tell us:

—Idiots! Gulfs! Brats! Donkeys! Marranos! Swine! Hooligans! Scoundrels! You little rascals! Criminals! Criminals!

Our neighbor is a woman younger than grandmother. She lives with her daughter in the last house in town. It is a shack completely in ruins, with the roof leaked in many places. There is a garden around it, but it is not cultivated like grandmother’s garden. Only weeds grow.

The neighbor spends the day sitting on a stool in her garden looking in front of her, no one knows what. At dusk, or when it rains, her daughter takes her by the arm and makes her enter the house. Sometimes her daughter forgets or is not there, and then her mother stays away from her all night, whatever the weather.

People say that our neighbor is crazy, that she lost her mind when the man who made her daughter abandoned her.

We know other children in the village. Since the school is closed, they spend the whole day outside. There are older ones and smaller ones. Some have their home and their mother here, others come from far away, like us. Especially from the city.

Many of these children are in the homes of people they did not know before. They must work in the fields and vineyards; the people who take care of them are not always kind to them.

Older children often attack younger ones. They take everything they have in their pockets and sometimes they even take off their clothes. They also beat them, especially those who come from outside. The children here are protected by their mother and never go out alone.

No one protects us. So we learn to defend ourselves from the elders.

Overnight, posters appear on the walls of the town. In one of them, an old man is seen lying on the ground with his body pierced by the bayonet of an enemy soldier. In another poster, an enemy soldier hits a child with another child he is holding by the feet. In another poster, an enemy soldier pulls a woman’s arm and with his other hand tears her blouse. The woman has her mouth open and her tears are running down her cheeks.

People who look at the posters are terrified.

The grandmother laughs and says:

-Which lies. Do not be afraid.

People say the city has fallen.

Back at grandma’s house, Lucas lies down next to the garden fence, in the shade of the bushes. He waits. An army vehicle stops in front of the border guards building. Some soldiers come down and leave a body wrapped in a camouflage tarp on the ground. A sergeant leaves the building, gives a signal and the soldiers remove the tarp. The sergeant whistles.

—Identifying him will not be a piece of cake, of course! You have to be an idiot to try to cross this fucking border and in broad daylight!

I’m in jail in the small town of my childhood.

It is not a real prison, but a cell in the local police building, a building that is just another house in the town, a one-story house.

In the past, the cell must have been a laundry room, since the door and window face the patio. Window bars were added on the inside to make it impossible to reach the glass and break it. In the corner, behind a curtain, is the toilet. Against one of the walls, there is a table and four chairs bolted to the floor and, on the opposite wall, four folding beds. Three of them are down.

I’m alone in the cell. There are few criminals in this city and, when one appears, they are immediately transferred to the neighboring city, which is the capital of the region, twenty kilometers from here.

I am not a criminal. If I am here it is because I do not have the papers in order and my visa has expired. Furthermore, I have incurred debts…

On October 30, I celebrate my birthday in one of the most popular taverns in the city with my drinking buddies. Everyone invites me to drink. There are couples who dance to the sound of my harmonica. Some women kiss me. I’m drunk. I start talking about my brother, like I always do when I drink too much. The whole city knows my story: I’m looking for my brother, with whom I lived here until I was fifteen. I have to find him here, I wait for him, I know that he will return when he finds out that I have returned from abroad.

Everything is a lie. I know perfectly well that in this city, in my grandmother’s house, I lived alone, that even then I imagined that there were two of us, my brother and I, to make the unbearable loneliness bearable.

There were always four of us at the table: our father, our mother and the two of us.

Our mother spent the day singing. In the kitchen, in the garden, in the patio. She also sang at night, in our room, so that we would fall asleep.

Our father didn’t sing. He sometimes whistled while splitting wood for the kitchen. In the afternoon, and even late at night, we heard him typing on her typewriter.

It was a pleasant and calming noise like music, like our mother’s sewing machine, like the clatter of dishes, like the singing of blackbirds in the garden, like the wind in the leaves of the wild vine that we had on the verandah. or in the branches of the walnut tree that grew in the patio.

When my mother receives the money, the small amount of money that the State gives her, she goes to the city and comes back loaded with expensive toys, which she hides under Lucas’s bed. She warns me:

Do not touch anything. Those toys should be new when Lucas comes back.

Now I know what medications my mother takes.

The nurse explained everything to me.

So, when she doesn’t want to take them or forgets, I put them in her coffee, tea or soup.

You are brothers, don’t forget it, Klaus. You cannot love each other the way you loved each other. I shouldn’t have taken you home.

Say:

—What does it matter that we are brothers? No one would know. We have a different last name.

—Don’t insist, Klaus, don’t insist. Forget Sarah.

I do not say anything. Antonia adds:

—I’m hoping for a boy. I have remarried.

Say:

—You want another man, you lead another life. Why do you keep coming to the cemetery?

—I don’t know, maybe I do it for you. You were my son for seven years.

My mother barely has any money. She receives a small amount from the State for disability. I am another burden for her. I must find a job as soon as possible. Véronique suggests that I deliver newspapers.

I get up at four in the morning, I go to the printing press, I pick up the bundle of newspapers, I walk through the streets assigned to me, I leave the newspapers in front of the doors, in the mailboxes or under the iron shutters of the stores.

My mother continually reproaches me for dropping out of school.

Lucas would have continued his studies. He would have been a doctor. A great doctor.

When the water pours through the roof of our dilapidated house, my mother says:

Lucas would have been an architect, a great architect.

When he showed her my first poems, my mother reads them and says:

Lucas would have been a writer, a great writer.

Un comentario en “Claus Y Lucas — Agota Kristof / Le Grand Cahier, La Preuve, Le Troisième Mensonge by Agota Kristof”