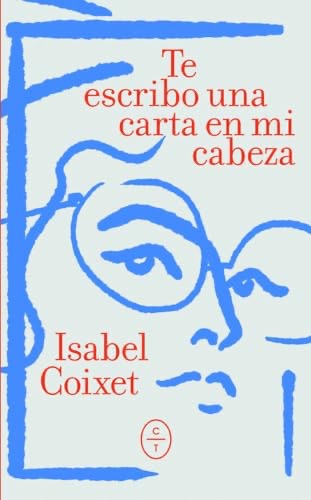

Interesantes reflexiones de esta directora de cine.

Ahora que se habla tanto de apropiación cultural, hay cosas que me parecen mucho más peligrosas y poco éticas, porque más que apropiación, son un latrocinio cultural: el mundo de los remakes y las revisiones de películas y series que se vuelven a rodar con idénticas tramas, pero con distintos actores y nuevas producciones… Creo que, hasta cierto punto, es normal que los creadores busquemos inspiración en el pasado, en otros autores y en otras obras. Pero sí hay algo que me indigna en todo esto: que la fuente original de una producción quede oscurecida por el morrazo que le echan unos cuantos para prácticamente atribuirse la creación de un formato que fue creado, genuinamente creado, antes que ellos nacieran.

– La escritura. Uno de los caminos más directos para empezar en el cine es la escritura. La estructura de una buena película está en un buen guion.

– El guion no es el tema. Un tema puede ser absolutamente fascinante, pero si no sabemos desarrollarlo puede ser una completa estupidez. Por el contrario, un tema o historia al que sobre el papel no le daríamos la menos importancia, con un guion bien armado puede resultar realmente fascinante.

– ¿Cómo empezar a escribir? Pues bien, empecemos por los personajes: edades, aspecto, pasado, presente, aspiraciones, ilusiones, traumas.¿Cómo empiezan la historia? ¿Cómo terminan? ¿Las cosas que les pasan les cambian? Eso es lo que llamamos arco dramático. Que puede ser también un arco inexistente: hay muchos personajes en la historia del cine cuya fatalidad es esa justamente: a pesar de los problemas, las tragedias y los giros de guion no aprenden nada, no cambian. Ahí reside su drama. También ocurre en la vida, ¿no os parece?

– Una vez tenemos claro los personajes, pasemos a la trama. ¿Qué les pasa? ¿Cómo se relacionan? ¿Son sociables? ¿Son asociales y solitarios? ¿Qué ven? ¿Cómo lo asimilan? ¿Cómo reaccionan? Estas preguntas se aplican tanto a una película intimista como a una comedia o a una película de acción.

– La base de un guion es la escaleta y la base de la escaleta es la imaginación

– Creo que es la pregunta que más veces me han hecho: ¿De dónde salen las ideas? ¿Es una cuestión de imaginación? ¿De inspiración? ¿De esfuerzo? ¿De insistencia? ¿De trabajo? En realidad, es todo eso junto. Las ideas vienen cuando estamos abiertos a ellas, cuando estamos a la escucha. A la escucha de las historias de los otros, de las conversaciones que oímos en los bares, en el supermercado, en el metro. De las narraciones, novelas, ensayos históricos que leemos. De estar a la escucha de nuestro propio yo, de estar en contacto con las cosas que nos conmueven, que nos hacen vibrar, que nos emocionan, que nos intrigan.

– Uno de los ejemplos para mí más gráficos del origen de las ideas es la definición que da el poeta conde de Lautréamont cuando le preguntan qué es la poesía. Él dice: “Es el encuentro de un paraguas y una máquina de coser en una mesa de quirófano”. Es decir, tenemos dos elementos que no tienen nada que ver en un lugar que no les corresponde… aparentemente, porque de repente esos elementos incongruentes pueden colisionar o podemos hacerlos encajar en nuestras cabezas. Se trata de estar abierto a considerar que cualquier cosa puede ser el desencadenante de una historia.

William Friedkin, el director de El exorcista, tenía métodos muy particulares para dirigir a los actores, y en esta película, rodada en 1973, no se privó de ello: ya Gene Hackman, aún después de ganar el Óscar con la anterior película de Friedkin, French Connection, dijo (y cumplió) que no volvería a trabajar con él. Le gustaba tiranizarlos y, si lo consideraba oportuno, incluso abofetearlos. Para rodar las escenas del interior de la casa de Regan, llegó a colocar equipos especiales de refrigeración en el interior para que la temperatura no llegará a los cero grados y así, al hablar, los actores expulsaban vaho y, en general, tenían un aspecto vulnerable y frágil. Como consecuencia, los miembros del equipo sufrieron toda clase de resfriados e incluso neumonías. El decorado se quemó varias veces sin que se supieran las razones. Otra de las cosas que hacía el director para crear tensión en el plató era de cuando en cuando sacar un rifle y disparar. Para rodar las escenas del padre Karras, aprovechó la tristeza real en el rostro del actor Jason Miller, cuyo hijo pequeño había tenido un accidente y se debatía entre la vida y la muerte.

La mancha humana, de Philip Roth, está ambientada en 1998 en los Estados Unidos, durante el período de las audiencias de impeachment del presidente Bill Clinton y el escándalo de Monica Lewinsky. Es la tercera de las novelas de posguerra de Roth que aborda grandes temas sociales, junto con La conjura contra América, siendo American Pastoral, a mi juicio, la mejor de ellas (y también a juicio del propio Roth).

La novela contiene un giro que, así como funciona perfectamente en el libro, falló estrepitosamente en su representación cinematográfica: resulta que, sin que nadie en su vida presente lo sepa, ni siquiera sus hijos, su protagonista, el profesor Coleman Silk, es negro, un afroamericano de piel clara que se ha hecho pasar por un judío blanco durante toda su vida adulta para evitar la discriminación.

Nunca me han gustado los juegos de azar. Poseo una mentalidad seudocalvinista: hay que ganarse las cosas con trabajo y esfuerzo, lo demás no tiene valor, sangre, sudor y lágrimas, etc., etc. Loterías, bonolotos, cupones, tómbolas o peregrinas inversiones en criptomonedas se me antojan maneras obscenas de ganar dinero. No entiendo el atractivo del bingo o del casino. El miedo es un sentimiento extraño porque, aunque es poderoso y constante, se le puede engañar y hasta domesticar, como uno de esos gatos salvajes que pueden comportarse dócilmente durante años y un día, de repente, la presencia de un chihuahua o la aparición de una pecera con peces rojos hace salir la bestia que llevan dentro. Y ese es el día que hay que temer de verdad, el día que los trucos ya no funcionen. Ese día tendré que recurrir a otro truco.

El gaslighting es una técnica de intimidación y manipulación mental como ninguna otra. El depredador descalifica sádicamente a su presa, una mujer, hasta el punto de hacerla dudar de su propia razón, invirtiendo los roles: él es la víctima, ella es el problema. Es un término que pasó al lenguaje común en Estados Unidos y que se inspira en el título de una magistral película de George Cukor, estrenada en 1944, Gaslight (Luz de gas). La historia se desarrolla en el siglo xix, una joven rica (Ingrid Bergman) casada con un hombre con un oscuro secreto (Charles Boyer), que la aísla, la manipula, la menosprecia hasta el punto de hacerla parecer loca a los ojos de su entorno: cada vez que se encuentra sola en casa, la luz de gas pierde intensidad, de manera inexplicable, como si alguien estuviera presente en la casa. El responsable, sin embargo, niega tajantemente esa presencia en la casa y la víctima acaba dudando de su propia cordura.

Me dejan sumamente perpleja y llena de admiración las personas que programan sus viajes a años vista: de aquí a un año y dos meses, te cuentan, harán un viaje a Vladivostok para ver un festival de esculturas de hielo, ya tienen los billetes y las reservas de hotel y hasta el nombre del guía que los llevará a dar una vuelta por los alrededores de la ciudad, que dicen son espectaculares. Nunca he sido capaz de nada por el estilo: me invade una sensación de opresión y desaliento paralizantes cuando he comprado un billete de avión a más de un mes vista (sí, ya sé que se consiguen mejores tarifas) o cuando en mi agenda aparecen eventos en los que se supone he de estar el año que viene. Pienso: ¿Me apetecerá dentro de tres meses algo a lo que he accedido hoy? Y sobre todo, ¿estaré viva?.

Interesting reflections from this film director. Nice reading

Now that there is so much talk about cultural appropriation, there are things that seem much more dangerous and unethical to me, because more than appropriation, they are cultural theft: the world of remakes and revisions of films and series that are reshot with identical plots, but with different actors and new productions… I think that, to a certain extent, it is normal for us creators to look for inspiration in the past, in other authors and in other works. But there is something that angers me in all this: that the original source of a production is obscured by the snub that a few people give it to practically take credit for the creation of a format that was created, genuinely created, before they were born.

– Writing. One of the most direct ways to start in cinema is writing. The structure of a good movie is in a good script.

– The script is not the issue. A topic can be absolutely fascinating, but if we don’t know how to develop it it can be completely stupid. On the contrary, a topic or story that on paper we would not give the least importance to, with a well-crafted script can be truly fascinating.

– How to start writing? Well, let’s start with the characters: ages, appearance, past, present, aspirations, illusions, traumas. How do they start the story? How do they end? Do the things that happen to them change them? That’s what we call a dramatic arc. Which could also be a non-existent arc: there are many characters in the history of cinema whose fatality is precisely that: despite the problems, the tragedies and the twists of the script, they do not learn anything, they do not change. Therein lies its drama. It happens in life too, don’t you think?

-Once we are clear about the characters, let’s move on to the plot. What’s wrong with them? How they relate? Are they sociable? Are they asocial and lonely? What do you see? How do they assimilate it? How do they react? These questions apply to an intimate film as well as a comedy or an action film.

– The basis of a script is the rundown and the base of the rundown is the imagination

I think it is the question that I have been asked most times: Where do ideas come from? Is it a question of imagination? Of inspiration? Of effort? Of insistence? Of work? Actually, it’s all of that together. Ideas come when we are open to them, when we are listening. Listening to others’ stories, to the conversations we hear in bars, in the supermarket, on the subway. From the stories, novels, historical essays that we read. To listen to our own self, to be in contact with the things that move us, that make us vibrate, that excite us, that intrigue us.

– One of the most graphic examples for me of the origin of ideas is the definition given by the poet Count de Lautréamont when asked what poetry is. He says: “It is the meeting of an umbrella and a sewing machine on an operating room table.” That is, we have two elements that have nothing to do with each other in a place that doesn’t belong… apparently, because suddenly those incongruent elements can collide or we can make them fit in our heads. It’s about being open to considering that anything can be the trigger for a story.

William Friedkin, the director of The Exorcist, had very particular methods for directing actors, and in this film, shot in 1973, he did not deprive himself of this: Gene Hackman, even after winning the Oscar with Friedkin’s previous film , French Connection, said (and delivered) that she would not work with him again. He liked to tyrannize them and, if he saw fit, even slap them. To film the scenes inside Regan’s house, he went so far as to place special cooling equipment inside so that the temperature would not reach zero degrees and so, when speaking, the actors expelled steam and, in general, looked vulnerable and fragile. As a result, the team members suffered all kinds of colds and even pneumonia. The set burned several times without knowing the reasons. Another thing the director did to create tension on the set was from time to time to take out a rifle and shoot. To film Father Karras’ scenes, he took advantage of the real sadness on the face of actor Jason Miller, whose young son had been in an accident and was torn between life and death.

The Human Stain, by Philip Roth, is set in 1998 in the United States, during the period of President Bill Clinton’s impeachment hearings and the Monica Lewinsky scandal. It is the third of Roth’s postwar novels to address major social themes, along with The Plot Against America, with American Pastoral being, in my opinion, the best of them (and also in Roth’s own opinion).

The novel contains a twist that, just as it works perfectly in the book, failed miserably in its cinematic representation: it turns out that, unknown to anyone in his present life, not even his children, its protagonist, Professor Coleman Silk, is black. , a light-skinned African American who has posed as a white Jew his entire adult life to avoid discrimination.

I have never liked games of chance. I have a pseudo-Calvinist mentality: things have to be earned with work and effort, the rest has no value, blood, sweat and tears, etc., etc. Lotteries, bonus lotos, coupons, raffles or strange investments in cryptocurrencies seem like obscene ways to make money. I don’t understand the appeal of bingo or casino. Fear is a strange feeling because, although it is powerful and constant, it can be tricked and even domesticated, like one of those wild cats that can behave docilely for years and one day, suddenly, the presence of a chihuahua or the appearance of A fish tank with red fish brings out the beast inside. And that is the day to truly fear, the day when tricks no longer work. That day I will have to resort to another trick.

Gaslighting is an intimidation and mental manipulation technique like no other. The predator sadistically disqualifies her prey, a woman, to the point of making her doubt her own reason, reversing the roles: he is the victim, she is the problem. It is a term that entered common language in the United States and is inspired by the title of a masterful film by George Cukor, released in 1944, Gaslight. The story takes place in the 19th century, a rich young woman (Ingrid Bergman) married to a man with a dark secret (Charles Boyer), who isolates her, manipulates her, belittles her to the point of making her seem crazy in the eyes of her family. environment: every time she is alone at home, the gas light loses intensity, inexplicably, as if someone were present in the house. The person responsible, however, categorically denies that presence in the house and the victim ends up doubting her own sanity.

People who plan their trips years in advance leave me extremely perplexed and full of admiration: in a year and two months, they tell you, they will take a trip to Vladivostok to see an ice sculpture festival, they already have the tickets and the hotel reservations and even the name of the guide who will take them on a tour around the city, which they say are spectacular. I have never been capable of anything like that: a paralyzing feeling of oppression and discouragement invades me when I have bought a plane ticket more than a month away (yes, I know that you can get better rates) or when events appear in my diary where I’m supposed to be next year. I think: Will I want something in three months that I agreed to today? And above all, will I be alive?